The new record is crushingly good. It ruined my whole month.

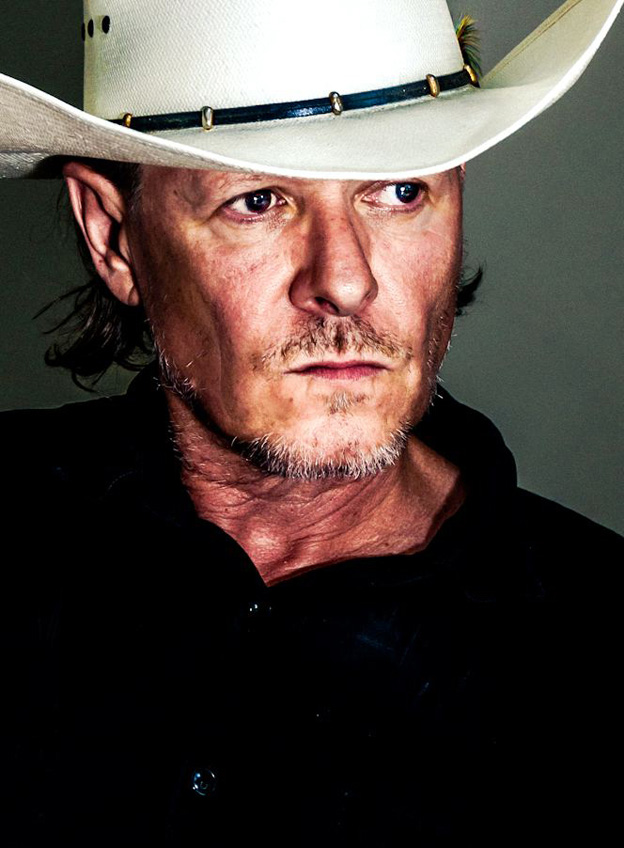

Photos by Samantha Marble

Swans: “Mother of the World”

Thirty years after forming Swans as a confrontational, industrial-tinged noise-rock outfit in New York City, Michael Gira’s making some of the best music of his career. The Seer, Swans’ 12th album overall and second since since Gira reconstituted the dormant group in 2010, features nearly two hours of time-stretching, transcendent drone and noise steeped in soulfully ecstatic, unrelenting blues repetitions: one piece tops 20 minutes, another 30, and there’s never a dull spot. The record pushes everything Swans have done well in the past to a logical extreme, and though it’s not the sort of music you’d expect from a man in his 50s, only someone with as much experience as Gira could pull it off.

The Seer finds Gira surrounded by the band who backed him on the tour for 2010’s My Father Will Guide Me up a Rope to the Sky; it’s a group of accomplished players who feel like a gang, or a family. And many of these songs were developed in live settings, much like the work of experimental composer La Monte Young‘s Theatre of Eternal Music— they’re pushing less for “rock” and more for art. (Full disclosure: I put on a Swans show in Brooklyn with a friend a few years ago.) That core’s been fleshed out with guest spots from, among others, Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Karen O, Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker of Low, members ofAkron/Family, Mercury Rev‘s Grasshopper, and– maybe most surprising to longtime fans– ex-Swan and Gira love interest/foil, Jarboe, who was absent from the last record. So: There’s a lot to unpack here.

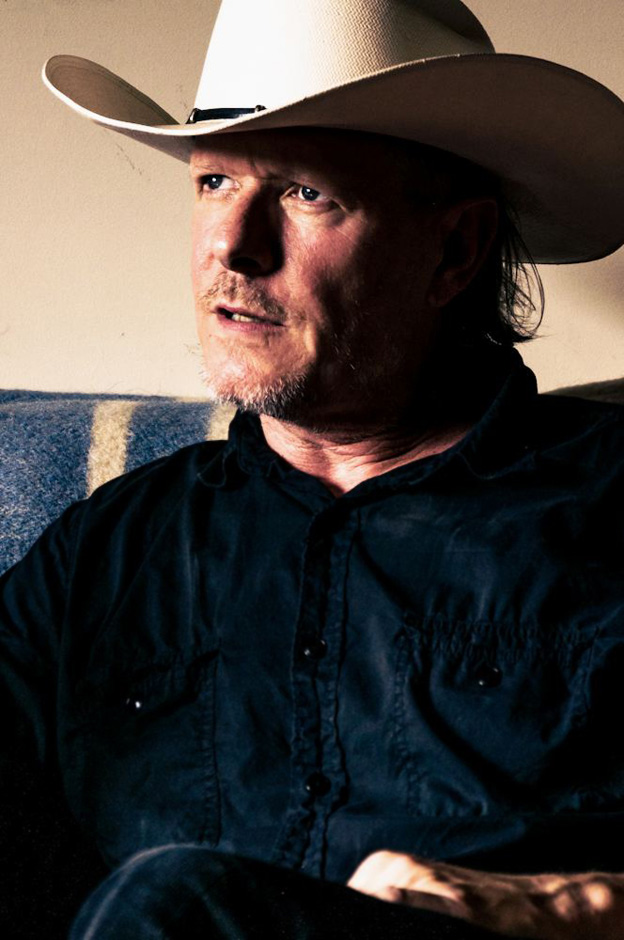

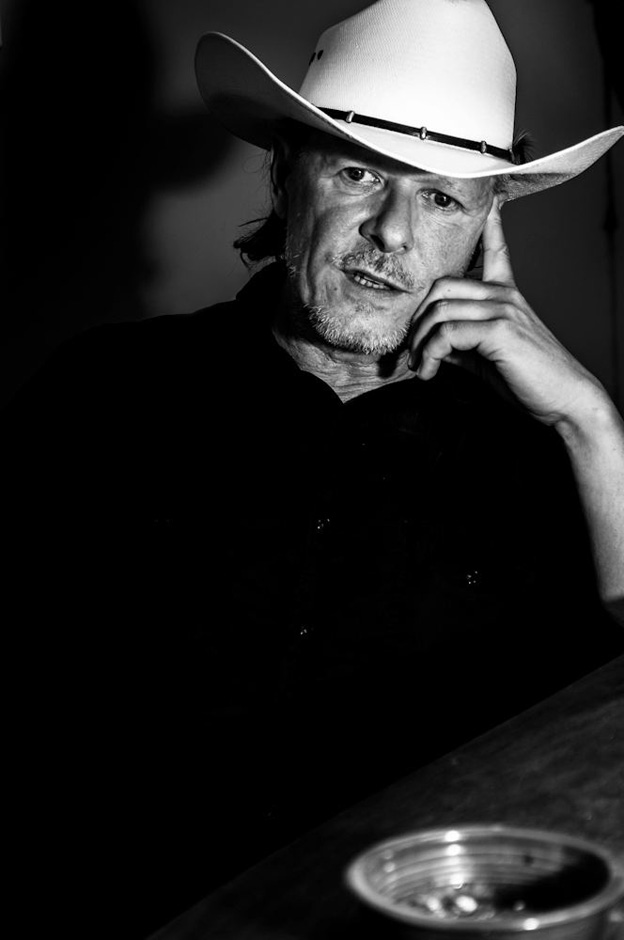

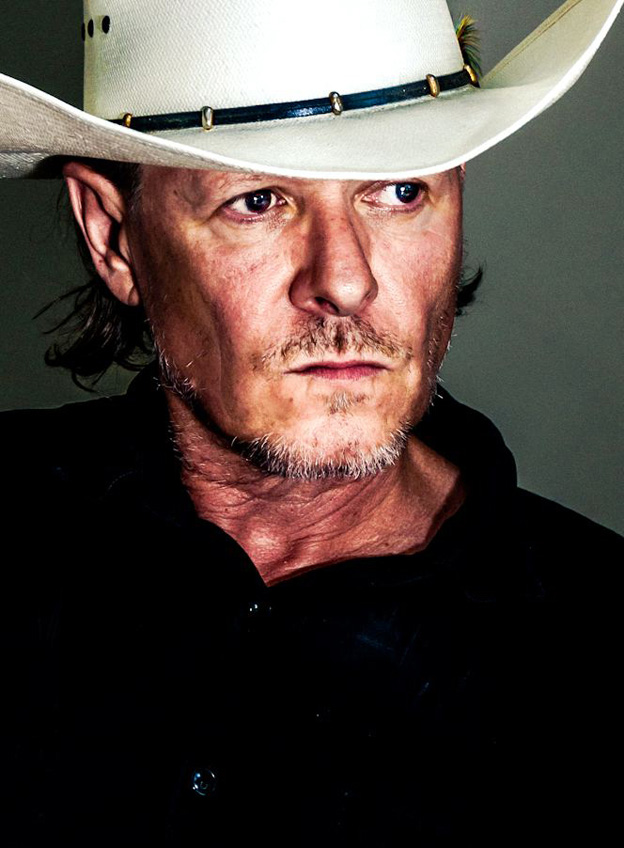

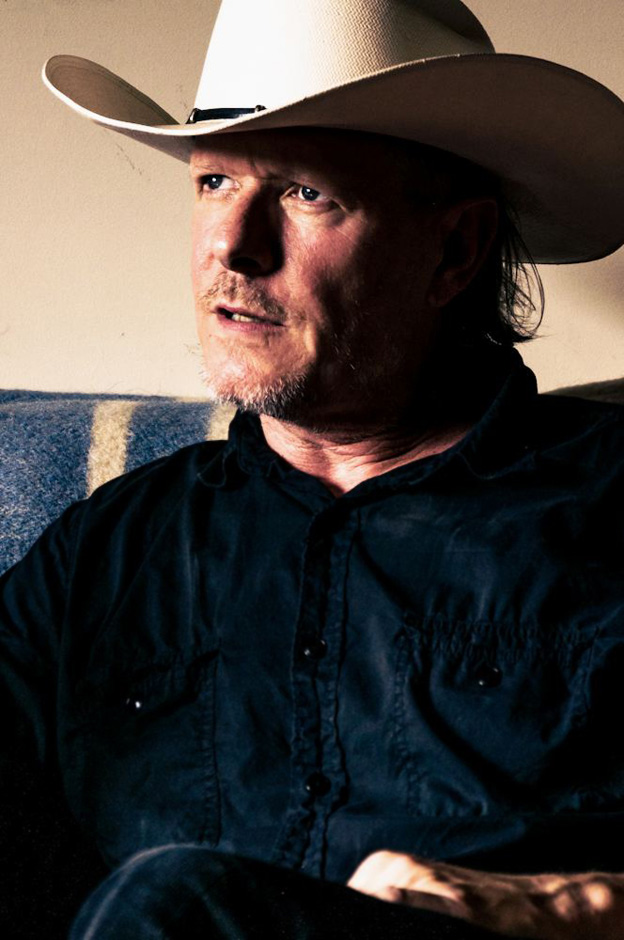

A couple of weeks ago, I drove to Gira’s home– a red wooden house on a hill– near Woodstock, N.Y. There’s art on the walls from his previous records. A guitar leans against a mural his children sketched and scribbled. The bookshelves are packed. The driveway’s made of dirt. There are a lot of trees.

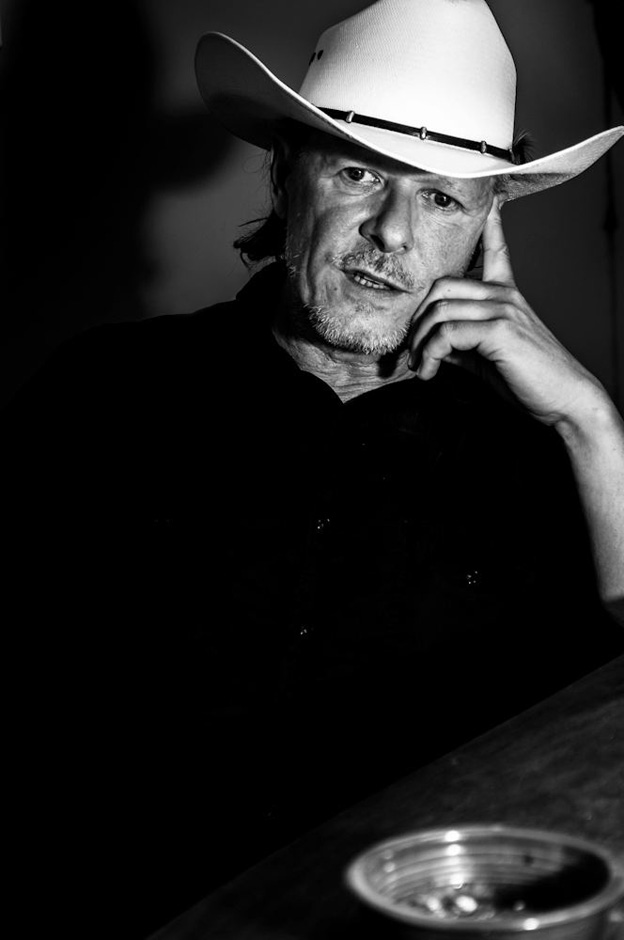

I first interviewed Gira almost a decade ago, and then, as now, he’s a generous, funny man, but one who clearly doesn’t suffer fools or foolishness. (And yes, he wore his cowboy hat.) We spent a couple of hours at the kitchen table talking about the past, present, and future. At one point, while we took a break to eat smoked meat and cheese, Gira mentioned his area was in the midst of a drought and pointed to a patch of burnt grass outside the window to prove his point. Not long after we shook hands goodbye, though, I got stuck in one of the biggest downpours I’ve experienced: As I headed back home to New York City, giant, blinding sheets of water slipped off the sides of the George Washington Bridge and onto my windshield. It felt like drowning.

Pitchfork: In a note you wrote about the new record, you call it a culmination of the past 30 years. What do you mean by that?

Michael Gira: I meant that a bit facetiously, but it really is, I suppose. In a way, it’s pretentious to say because really everything— even me breathing right now– is a culmination of 30 years… actually, 50-something years. [laughs] But the album uses all the tropes, tools, aesthetics, atmospheres, and methods I’ve gleaned as a producer and working with this band over the last 30 years. On this record in particular, I didn’t want to give up until we had reached the absolute limit of my capabilities– and we paid a heavy price. [laughs]

“The music takes you. It has to be alive.

It’s like you hammer something, and the way

it happens to bleed leads you into new directions.”

Pitchfork: There’s a 30-minute song on there, a couple 20-minute songs; it’s almost three times as long as your last album. It feels especially intense.

MG: With last album, all these people had not played together before– we kind of just threw the dice. Turns out we got along great. So, for this one, we had toured for a year, and much of the material– including the 30-minute song, “The Seer”– developed on the road. It started out with an idea I had– maybe on acoustic guitar, maybe just a rhythm idea– and it gradually metastasized into what it eventually became through playing live.

With the last record, I regretted not letting certain things develop. So I had this idea of no restrictions on this one because, really, who do I have to answer to? No one. I have my own record company. I have to answer to God, basically. I’m not young, so I want to make the best possible work I can before I exit. [laughs]

Pitchfork: There’s this improvisational feel with some of these songs– when you play “The Seer” live, is it going to be something that’s 30 minutes every time or could it expand to an hour?

MG: It’s gonna expand– though I don’t think “improvisation” is even the correct term. It’s more like you just hammer something, and the way it happens to bleed leads you into new directions. The music takes you. It has to be alive. If we got up there and just tried to parrot the record, I’d be really disappointed in myself.

Pitchfork: There are parts of the new record that remind me of Glenn Branca: these repetitious, real-time loops and pulsations. Is that an influence here?

MG: Not specifically, though I love Glenn’s music and there is an aspiration toward this kind of peak experience that I really admire in him. I played one concert with him in the early 80s and I learned a lot by just watching him gather this disparate group of people together and, in a very short amount of time, becoming a complete dictator towards the laudable goal of trying to reach ecstasy. And he achieved it. It was really impressive and inspirational to me, more now than back then, even.

But I also see similarities between this music and Ummagumma-era Pink Floyd, too. But it’s different; it’s Swans. I don’t want to sound like everybody else. I like loud electric guitars because I like how you can just lose your entire being in the sound. But I can’t find myself in a situation where we’re doing typical chord progressions– it just seems cliché to me. Even changing chords sounds like a cliché sometimes, though it happens occasionally in our music. [laughs] But you find ways to push yourself into the sound through repetition. It doesn’t stay the same. It morphs constantly.

Swans: “The Apostate”

Pitchfork: People associate Swans with darkness, but The Seer ends with “The Apostate”: “We are blessed. We are blessed. Fuck bliss. Fuck bliss.” It feels like an ecstatic moment.

MG: From this last experience of touring so intensively, the shows became totally immersive. It’s this sound that takes your body, mind, and spirit. You’re not really playing it. I realized that was the core of what I wanted. It’s not such an unusual thing. I think the Stooges or Pink Floyd say that same thing. But yeah, it’s the ambition to rock… happily. [laughs]

Pitchfork: You’ve always had a wit and humor about you, how important is that to Swans?

MG: People always consider us to be very dour and depressing, but fuck that shit. The goal is ecstasy, but I don’t want to make some sort of saccharine pop music. I want to make something that’s completely uncompromising: the best possible music ever made. [laughs] I don’t take myself too seriously, hopefully.

Pitchfork: In early interviews, you talked about playing live as a physical experience. How much does that aspect of music still drive you?

MG: Very much so. But not just like a cheap Motel 6 fuck; I’ve used the analogy of tantric sex. It’s like being completely selfless while you find yourself simultaneously. Weirdly, I just readthis long piece in The New Yorker with Bruce Springsteen and he said the same thing.

Pitchfork: Have you seen the YouTube video of Springsteen running into the audience and guzzling a beer and then continuing to play?

MG: I’m surprised he drinks. I don’t know how he does what he does physically. Jesus. He has a personal trainer, of course, like people of his zeal might. But it’s very physical and spiritual.

Pitchfork: As you get older, how does your on-stage physicality shift?

MG: I have a healthy fear of breaking my bones now. I used to not think about that– I would routinely break my ribs doing stupid things, just feeling the music so much that I would throw myself down on the monitors. It fucking hurts. [laughs] I used to have to wear these bandages around my belly and every time I shouted it was just immense pain. I broke my tooth on a microphone. Stupid things. I don’t throw my body down on the stage at all anymore because I’m sure I’d snap like a twig. But it is still a physical commitment. All we’re really doing is holding this piece of wood, but it’s the way you slam your body into it, the intensity. The heat on stage is a big factor, too. It’s very physically draining.

“I used to routinely break my ribs doing stupid things onstage,

but I have a healthy fear of breaking my bones now.”

Pitchfork: When you were doing your solo tours, you’d include the old Swans song “God Damn the Sun”, which has an end-of-innocence theme. And there’s the playful– but ultimately exploded– rabbit on the cover on White Light from the Mouth of Infinity. And the idea of childhood or innocence shows up again on this new record, too.

MG: If there’s any kind of lyrical thread in the record, it’s childhood. I don’t know if that’s because I’m nearing senility [laughs], or because I feel an affinity for an infant, or if it’s something I think about because I have young children. But that is there. At a certain age, children are total Id– they’re anything but beautiful little flowers. That always interests me. The place where the ego and the superego start, and where guilt and socialization and morality takes place, the true root of it.

Pitchfork: Is that something you were interested in even before you had kids?

MG: Well, I wrote a story 20 years ago, which I just re-read. It’s pretty disturbing; it’s called “The Coward”. It’s about a young man who’s asleep in his bed. His brother’s daughter is out in the other room. The man has to pee, so he has this piss erection. He hears the girl come in and she starts dancing on his bed and he has this erection, and it’s really uncomfortable. He sends her out, and he passes out. He’s drunk. Then he wakes up and hears this sound– someone has come in and is raping the girl, and he walks out to the corner and peaks around and sees it and doesn’t do anything because he’s too cowardly. He goes back to bed. That’s how it ends. Now, having a child, it really disturbs me. [laughs] It was just that question of where morality begins. The sexuality of children– there’s a lot friction there. That tension interests me a lot.

Pitchfork: When Swans started up again a few years ago, you were very specific about saying that it wasn’t a reunion– it was a “reconstitution.” At the time, I thought it was just a semantic thing, but between the last album and The Seer, it doesn’t feel like a reunion. It feels like a new direction.

MG: That was exactly why I reconstituted Swans: I wanted to challenge myself and move into something new. I felt that using the name Swans and the sonic attitude that that engenders was what I needed to move forward musically, and it’s led to lots of new things. In this month of rehearsals we just did, we came up with three new pieces that last 45 minutes or an hour in total. We’re heading more into this territory of the groove, but not some kind of white-boy funk. [laughs] They’re pretty strange, fractured grooves.

You’ll see when you see us live. The first song in the set is a new one called “To Be Kind”. It starts out very quiet and then it goes into these huge, rolling sonic waves, without drums– maybe it’s only like seven or eight minutes. The other couple songs are probably 15 minutes each. It’s just organically what needs to happen in the music.

“If they asked us to do a concert of old Swans songs, we would say yes and then play the entire Creedence Clearwater Revival box set.”

Pitchfork: I think I know the answer to this, but with all those Don’t Look Backshows where bands play their classic material, would you ever perform a set of old Swans songs?

MG: If they asked us to do that– and I’m sure they won’t– we would say yes and then play the entire Creedence Clearwater Revival box set. [laughs] Playing an old record doesn’t interest me at all. It’s exactly the opposite of what I want to do.

Pitchfork: As far as nostalgia goes, what do you think is poisonous, or not interesting, about it?

MG: It just puts you in this box and makes the current work you’re doing less– it limits you to one specific aspect of the work. I’m always trying to push myself into unfamiliar places with the music, sometimes without success, I have to admit. But I’d rather be there than relying on a style that people recognize and want to follow. It wouldn’t interest me to try to sound likeCop or something. It would be silly and soul-crushing.

Pitchfork: Are you going to play old Swans material on the upcoming tour?

MG: Just one song. Last time we did two or three, and I began to feel a little inauthentic about it halfway through the tour, so we started dropping them. Now we’re trying this song “Coward”, which Swans did in 1985– I’m attracted to its really weird groove. We’re taking it apart and trying to find something new in it.

Pitchfork: At this point, Swans is more popular than ever and you’re playing these bigger shows. Did you expect that? Was it a happy accident?

MG: Yeah, I had no idea what to expect. I did it because I needed, for my own personal selfishness, a way to keep working that was challenging and felt vital. I’m very fortunate that, through the auspices of the nefarious internet, the music has reached people that have an inclination towards this kind of thing much more so than it would have 20 years ago.

It’s good that people come to the shows because there’s nothing fashionable about us. Never has been, really. We’ve never been part of a scene. So the people that come are really there for the music. Fortunately, there’s a lot of young people and a burgeoning female contingent, which is good as well.

Pitchfork: What has it been like for you to play these bigger spaces with, it seems, more at stake?

MG: As far as playing playing festivals and everything, I feel like that’s what I was born to do. I’m an entertainer, hopefully in the best sense. Nina Simone was an entertainer. Bob Dylan was an entertainer. Anyone that can occupy a piece of music and make the air catch on fire at that moment is a true entertainer. That’s how I view it. That’s what I was meant to do. I love doing it. That’s why I’m on earth.

Pitchfork: With all this new interest in the band, have you been offered any weird commercial opportunities?

MG: [laughs] I haven’t been allowed that possibility. I’m not sure what I would do. Obviously, I’m not rich. I could use some money. But it would be a moral decision: I have obligations to certain hopeless dependents, so I would have to weigh the two options. But I don’t think that’s going to happen, considering the music. I really wish some very successful filmmaker would approach me about doing a soundtrack, but it’s never happened. I don’t have agents working on that kind of shit.

“Anyone that can occupy a piece of music live and make

the air catch on fire at that moment is a true entertainer.

That’s what I was meant to do. I love doing it.”

Pitchfork: How did Karen O end up on The Seer?

MG: I used to see Karen at Flux Information Sciences shows– that’s the group I released 10 years ago. I was always impressed with her because she was like the lone punk chick thrashing about with no self consciousness about anyone else around her. She was just completely into the music, by herself. She reminded me of numerous punk chicks of the 70s. Seeing these really strong females responding to rock in that way is really great. I remembered her.

And it turns out that our bass player, Chris Pravdica, is friends with them. I had written this song, “Song for a Warrior”, and I was singing it, but I felt my voice was this horrible intrusion on what was a good song, because it’s anything but mellifluous. Since the song is like a country lullaby, I thought it would be appropriate for a female. Chris pointed me to a few of Karen’s solo works where she sings in this really gentle, compassionate, soulful way, and I asked her to do it. She agreed immediately. It turned out really well. I was happy to have her.

Pitchfork: A lot of the things that happened during the period when you moved to New York in 1979 come back every few years; there was a 2004 documentary that you were featured in called Kill Your Idols that compared the late-70s/early-80s art-punk scene with early 2000s bands like Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Black Dice.

MG: Yeah, it was a strange premise. Those two things don’t have anything to do with each other, as far as I’m concerned. I guess it was to show the difference between New York then, which was a really hard-ass place, and now. You kids don’t know. [laughs] It was really hard to survive as an artist. I literally had holes in my shoes and went without eating often. But so be it. That’s how it was. It was cold. The people that survived and made something really had to be talented and megalomaniacal and devoted. Now– nothing against the current generation or anything– but [music] seems like more of a career option thing. [laughs]

Pitchfork: Early on, I imagine you were very influenced by your surroundings in New York. Does the idea of New York have any effect on Swans now?

MG: None whatsoever. And I would’ve vehemently opposed that depiction of us then, too. But now I’m humble enough to admit that the environment did have an effect. But it was just this need to roar that was inside me and my friends– but not in any kind of typical way. I really wanted to get to the animal core of rock music and eliminate anything that wasn’t necessary.

It was an important time in my life, and it was a great period musically. It’s probably my own mental malady, but when I walk around New York now, there are so many ghosts. I find it very uncomfortable. There were many hard years, and I never really achieved any kind of comfortable financial success, so I just associate it with struggle. When I had a chance to get out, I was elated.

“I really wanted to get to the animal core of rock music

and eliminate anything that wasn’t necessary.”

Pitchfork: Former Swan Jarboe was not on the last record, but she is on this one. I remember when the band was originally reconstituted, a lot of people were pretty vocal about her absence.

MG: Well, fuck that shit. I don’t really care about that. It’s just noise.

Pitchfork: How did she come back into the fold?

MG: We saw each other when we played Atlanta, and it was great to see her. I always love her and think she’s very talented, and I needed some female vocals doing these kind of drone chords. I thought of her because she has a really powerful voice and can still sound soulful at the same time. So I just asked her to do it, and she agreed. As far as her being in the band, that’s never going to happen. That would make it head into nostalgia land.

Pitchfork: Was there just not a place for her on the last album?

MG: Yeah, we wanted it to be a man record. [laughs]

Pitchfork: Speaking of, in the press materials for The Seer, you talk about “the men” in the band being “stellar men.” Then you released that press photo of you guys all sitting in the pool— it’s all very masculine.

MG: We’re all really good friends. This is, in terms of people getting along and committing to the goals of what we want the sound to be, the best group I’ve ever had. I wouldn’t be so presumptuous as to say it’s the best music ever, although I like it the best. But just in terms of being a band and people really caring about what’s happening onstage, it’s definitely the best.

Pitchfork: How does The Seer‘s cover tie into the record?

MG: My dear best friend Simon Henwood, the artist, is a great resource. He had this little tempera painting of a wolf-like thing, and I asked him to develop it. He put my teeth in without telling me. Then I asked him: “Why don’t you put this sort of exploding… posterior.” [laughs] It just seemed to fit. I don’t know how it ties in content-wise. It can’t answer the questions; it shouldn’t answer the questions. It should create more questions. I think it does.

Pitchfork: You funded the record through the sales of a live CD, We Rose From Your Bed With the Sun in Our Head. Why did you decide to do that?

MG: Necessity. I’ve survived since I was 14 by working construction jobs, whatever it took, and I will continue to survive and have something of a productive life just figuring out how to fucking do it. I started making handmade CDs in the 90s to try to help fund records. It’s just one way of doing it. With the increase of internet piracy, it’s a growing necessity to do things like this. I’m not saying that I enjoy it, but I’m capable. I know how to work. Making those CDs, signing them, numbering them, packing them. It takes hundreds of hours, but it’s worth it because I’m able to do the thing I love.

Pitchfork: To raise money, you also recorded personalized songs for people who gave $500. What was it like making those songs for people?

MG: They came easier than any song I can remember in 20 years. [laughs] But I guess it’s because I realized there would be no scrutiny. They were just gifts.

Pitchfork: Has anyone uploaded any of those to the internet?

MG: No. I’d be absolutely furious if someone did. It’s meant to be a very personal thank you. Those people contributed a lot of money, and I wanted to give them something that they could hold on to.

Pitchfork: With Swans being this full time thing now, are you still going to be able to put out other records on your label, Young God?

MG: No. That’s done. Maybe in the future I’ll put out someone’s one-off project, but generally I don’t have time. Also, unless you’re a pretty big indie, running a record label is fucking bleak. I started to really feel it as Akron/Family ascended– I saw the money still going down. I connected the dots and it was obvious that their audience was growing exponentially and their sales were low compared to the audience. It seems like it’s a fruitless task at this point.

“Unless you’re a pretty big indie,

running a record label is fucking bleak.”

Pitchfork: When you were putting out other people’s records, how much input did you have on how they came out?

MG: As much as I could force them into accepting. [laughs] I’m a producer in the old-school way– not just some slacker working on Pro Tools. I got involved, for the most part, in the actual song construction, lyrics even. I didn’t want to write the lyrics, but if there was a howler in there, I definitely pointed it out. Just trying to bring it up to a higher level. Of course, after a couple records, people get fed up with that. That’s fine.

Pitchfork: Watching Swans live, it often feels like you’re a conductor.

MG: Yeah, I mean, that’s my role. I’m the band leader. That’s not to say that the other people are my minions– they all put in a tremendous amount of personality, and push the music in ways I would never expect. Sometimes, I have to rein things in, turn things in a different direction, or, if I don’t like something, we have to argue about it. But that’s my job. Howlin’ Wolf was a bandleader. James Brown was a bandleader. I’m the band leader.

Pitchfork: I’ve always wanted to ask what your tour with Sonic Youth in 1982 was like.

MG: We called it the Savage Blunder tour, which sorta describes it. It was completely inept; we booked ourselves. No one knew who the fuck either of us were. We went out and people were just appalled, particularly with Swans. Sonic Youth had a few more recognizable rock elements in their music. They were much more accessible. I admit that. Good for them. In fact, they never wanted to go on after us, because everybody would be gone already. [laughs]

Pitchfork: There are stories about people walking out of early shows; now you’re playing sold-out venues. Does it feel like a vindication?

MG: It feels great. I don’t know about a vindication because there is no such thing. It just is what is. You make your work and you can’t ask for approval when you’re doing it. Otherwise, it’s going to be untruthful in some way. When audiences come now, they seem to be getting as much from it as we are. That’s fulfilling. This next tour, we’re not going to be rehashing what we did the last tour. I’m pretty confident that people are going to come along for the ride. If they don’t, tough.